Integrating the OECD Core Competency Framework into the Israeli Education System:A Real-Life Model Bridging Pedagogy and the Real WorldIntroduction

- sharon mayo

- Nov 24

- 19 min read

In recent decades, education systems around the world have been grappling with profound changes in social, technological, and economic environments. Globalization, the information revolution, climate change, unpredictable labor market dynamics, and demographic shifts are creating new challenges for learners in the 21st century (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018). The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that 65% of children entering primary school today will have jobs that do not yet exist (Zahidi, 2017).

Since 2015, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been leading a global initiative, known as the OECD Learning Compass 2030, to promote education for the future. This framework provides an up-to-date concept of 21st-century competencies that outlines the desired profile of graduates from education systems in the coming decades. It articulates an ambitious vision of the learner as someone capable of navigating the world in an informed and ethical manner, while flourishing as an individual and as a member of the community. However, the transition from a visionary statement to practical implementation in classrooms and schools is far from straightforward. Embracing the concept of competencies necessitates reforms in pedagogy, curricula, assessment methods, and the broader school culture.

In light of these challenges, it is increasingly evident that contemporary education must foster not only disciplinary knowledge in learners, but also competencies, that is, a set of abilities encompassing knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that enable individuals to navigate the complex modern world. Without corresponding changes in education systems, there is growing concern that graduates will be inadequately prepared for the demands of the mid-21st century, with potentially serious consequences for both individual development as well as economic and social well-being.

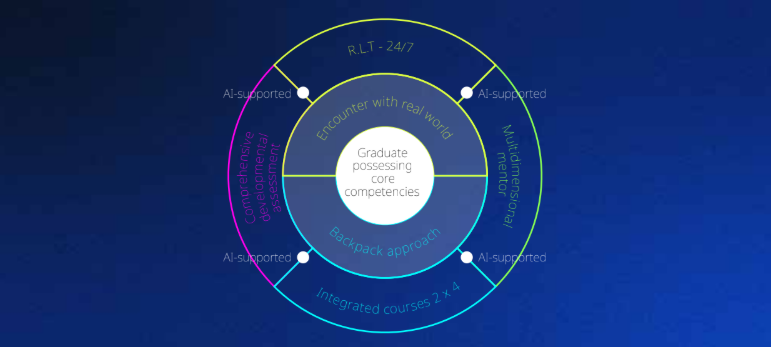

The first part of this article analyzes the concept of competencies, as articulated in the OECD's Learning Compass 2030, and its implications for education in the 21st century. The second part presents an innovative and “real-life” applied model that translates the concept of competencies into a transformative change within the school environment. This model emphasizes the integration of pedagogy with real-life contexts (the "backpack" principle) as proposed by the R&D Division of Israel’s Ministry of Education for implementation in schools across Israel.

The Concept of Competencies in the OECD Learning Compass 2030

OECD literature defines competencies as “ the mobilisation of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to meet complex demands" (OECD, 2018). In other words, competence is a holistic ability that enables individuals to function effectively in diverse real-life situations, extending beyond mere mastery of academic knowledge.

Accordingly, the Learning Compass 2030 framework emphasizes that learner development should include four key components: knowledge (e.g. disciplinary and factual knowledge); skills (e.g., critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and problem solving), values (moral values, ethics, democracy, etc.) and attitudes (personal and social attitudes, curiosity, perseverance, open-mindedness, etc.). These components are integrated within each competency, enabling its practical application. This cross-disciplinary approach requires a shift from the traditional teaching paradigm (based on knowledge transfer) to an active learning paradigm, in which the student develops and practices a range of competencies in meaningful contexts.

As an initial step in adapting the concept for practical implementation, developers of the Real-Life Model, which will be detailed below, defined the competencies as such:

Competency is a synergistic mix of four components that are grounded in the individual’s personal makeup, enabling (knowledge and skills) and motivating them (values and attitudes) to take proactive steps that will help them cope successfully over time with complex challenges in evolving realities.

Other countries have introduced similar frameworks of key competencies into their education systems. For example, New Zealand‘s curriculum defines five key student skills: thinking; using language, symbols and text; self-management; relating to others, and participating and contributing, which are integrated across all subjects. Finland also updated its curriculum (2016) to include seven transversal skills (such as thinking culture, multilingual competence, technological literacy, creative work, global responsibility, etc.) as an integral part of the learning content. These policy changes indicate a growing global recognition of the importance of equipping graduates with a wide range of capabilities that extend beyond narrow academic knowledge (Halinen, 2018).

In addition to core competencies, the OECD’s Learning Compass 2030 defines three interdisciplinary "transformational competencies" that are critical to shaping a desirable future in an uncertain world: a) Creating new value: an ability to initiate, innovate and create ideas, solutions and added value for society and the economy; b) Resolving tensions and dilemmas: an ability to bridge opposing perspectives, manage conflicts, and make informed decisions in situations of uncertainty and moral dilemma; and c) Taking responsibility: a willingness to act in a personally and socially responsible manner, to consider the consequences of one's actions, and to be committed to the well-being of others and the environment. These competencies assist learners in coping with situations of instability and ambiguity, fostering new attitudes and values and enabling moral decision-making with an awareness of possible consequences. They constitute educational goals because, without these competencies, individuals may be ill-equipped to pursue personal and social prosperity in the 21st century. Notably, these competencies are designed not only to prepare graduates to respond to changes, but also to empower them as agents of change, promoting innovation, building bridges between individuals and communities, and working for a sustainable and brighter future.

The practical application of these competencies often necessitates changes in teaching methods and learning content, but does not necessarily require the addition of new subjects. OECD literature emphasizes that competency development should be integrated into existing subjects to avoid further burdening the curriculum. For example, financial literacy can be integrated into mathematics and economics classes, critical thinking and teamwork embedded within multidisciplinary projects, and global literacy developed through geography and social science classes, rather than taught in separate lessons. This trend reflects a shift from the concept of knowledge transmission to the cultivation of learners capable of applying knowledge and skills in diverse, real-world contexts, thereby better preparing them for the challenges of the 21st century (OECD, 2018).

The Real-Life Applied Model: Bridging Pedagogy and the Real World

The Real-Life Model was developed in the R&D Division of the Israeli Ministry of Education as a proposal for a school based on the competencies approach. This model seeks to translate the principles of the OECD Learning Compass 2030 into practical activities within the school environment, aiming to cultivate in students the competencies outlined in the OECD’s innovative educational framework. The main approach in the Real-Life Model is authentic experiential learning based on direct engagement with real-world situations, not only in the classroom. This concept assumes that competencies (skills, knowledge, attitudes and values) are built and developed most profoundly when the learner actively explores real-world situations, deals with real-life problems and gains meaningful insights from every experience.

Notably, this approach of integrating learning with real-world situations echoes principles of progressive education that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. Philosopher John Dewey, whose ideas inspired this form of education, argued that “education is a process of living and not a preparation for future living.” His teachings reflect the idea that schools are, in fact, a microcosm of the real world, where children learn from active experience and not just from books (Dewey, 1897).

The Real-Life Project launched in 2025 in collaboration with eight partner schools selected from dozens l that responded to the call for participation. These schools are serving as co-developers and are engaging in a lean trial of the model with students–learning the approach and implementing select principles in practice. The project’s purpose is to test and refine the model, and the schools’ conclusions have informed a set of leading principles, as detailed below.

Guidelines for School Principals Implementing the Real-Life Model for Developing Competencies

The backpack principle, in other words, the educational process must be directly linked to the real world.

Personalization: competencies develop in individuals in different manners and degrees, and therefore, the instruction of competencies must be personalized.

Instruction: The teacher’s role is primarily to support and guide learners as they navigate their way and develop various building blocks, which will eventually be combined into full competencies.

The pedagogical domain: A transition from disciplinary classes to integrated courses that develop building blocks from the four components of competencies, while implementing R.L.T.- based learning methods.

The organizational sphere: A system based on personal choice; personal learning tracks that extend beyond school hours; and learning environments that are linked to real-world situations.

Assessment: The learner is evaluated on each of the building blocks of the four components of competencies, and this evaluation is conducted on an ongoing basis. These assessments enable the student to understand where they stand and plan ahead.

The Backpack Principle: Ongoing Learning in a Real-World Environment

A fundamental principle of the Real-Life Model is the understanding that student learning and development occur all the time and everywhere, and not just during a formal lesson in the classroom. The student gains experience through every interaction with their environment: at home, at school, and in all other places where life takes place outside the walls of educational institutions, in other words, 24 hours a day. At any given moment, the individual is exposed to new ideas, people, and situations, and these encounters offer learning and development opportunities: knowledge that can be gained, skills that can be practiced, moral dilemmas, and emotional reactions. All of these experiences contribute to the learner's development and enrich the "building blocks" of their competencies.

Based on this understanding, the Real-Life Model proposed the backpack as a metaphor for the learner's continuous development process. Similar to the physical backpack that a student carries on their back, this model simulates a virtual backpack that the learner carries with them at all times, which holds all the insights and learning experiences that they have accumulated and incorporated. Metaphorically speaking, every activity, in or outside of school, is collected in this bag as building blocks of learning: pieces of knowledge acquired, skills practiced, as well as social-psychological insights (attitudes) and moral lessons learned. The model posits that every meaningful learning experience must be identified and defined as a building block of this kind and classified into one of four categories of components: knowledge, skills, values or attitudes. In this way, experiential learning takes on structure and meaning: the student and his teachers interpret, process and embed what is learned from each experience and how it contributes to the development of the learner’s competencies.

The schoolbag principle creates a paradigm shift in the perception of time and space within the learning process. Instead of perceiving time spent outside the classroom as "lost time" from an educational perspective, the school assumes that every activity and experience can contribute to learning. Learning is no longer limited to formal classroom lessons; rather, it occurs all the time and everywhere. This creates a direct connection between school and the real world. The events and challenges that students experience in their natural environment serve as learning content in the full sense of the word. The teacher (or "mentor") and the student work together as "learning sensors." They identify everyday situations with learning potential, and discuss and analyze them, thus transforming the raw experience into conscious and structured learning. For example, a student who encounters a challenging social situation during recess or in an informal education setting discusses it with the teacher; together they identify what new knowledge the learner gained, what social skill they used, what values were underlined, and how these insights can inform future actions. The backpack, therefore, serves as a reflective tool, making sure that the learners maximize the developmental potential inherent in every experience. The underlying assumption is that, over time, the overall balance will be positive. Every day, a new experience or insight is added to the learner's collection, contributing to skill development. (Even if the experience was a negative or difficult one, it still promotes learning that is added to the backpack).

The backpack approach also blurs the boundary between formal and informal learning. Students are encouraged to bring their experiences, questions and curiosities from outside the classroom into the training environment. Conversely, they are prompted to take home the tools and stimuli acquired at school to engage in independent exploration beyond school hours. This approach positions the school as an open and flexible learning space that is integrated into the community and everyday life. A learner experienced in using the Real-Life Model can effectively engage in self-reflection and environmental observation and identify opportunities for continuous learning even without direct teacher mediation. The model deliberately fosters metacognitive abilities, enabling learners to reflect on their experiences and analyze their progress. In fact, one of the goals of the model is to develop students’ capacity to learn how to learn in open environments by recognizing their strengths and weaknesses, setting personal goals for themselves, and planning how to achieve these objectives by utilizing available learning resources across all areas of their life.

Personalized Learning and the Learner's Personal Journey

An essential principle that complements the backpack approach is personalized learning, which assumes that each student is unique in terms of talents, inclinations, learning style, and pace. Therefore, beyond collaborative learning, the model also focuses on the personal journey of each learner. Competencies develop differently among individuals – in both manner and degree - necessitating a direct emphasis on each student’s personal development through the guidance of a mentor. Based on the backpack concept, each student embarks on a unique developmental path, collecting building blocks throughout life that shape their distinct personal identity and personality. In fact, the unique combination of knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that an individual accumulates throughout life forms a "personal essence." This essence drives self-fulfillment in one area or another and influences the development of competencies based on the various building blocks and the personal interpretations unique to each person. Therefore, a school seeking to foster competencies should provide room for the unique personal development of each student, according to their unique profile.

In the Real-Life Model, the principle of personalized learning has several expressions. First, as described above, personal learning goals (daily, weekly and long-term) are defined for each student according to their current situation, essence and aspirations. The student is involved in setting these goals in a way that fosters intrinsic motivation and a sense of responsibility. Second, learners are given meaningful opportunities to choose among project topics, areas of specialization and modes of expression, allowing them to steer their learning along a path that suits them. Thus, in a Real-Life Model school, adolescents may choose to intern or volunteer in a professional field that interests them (such as a software company, a research laboratory, or a community initiative) as an integral part of the curriculum. Such a move provides each student with the opportunity to be in the "right place" for them, that is, in an environment where their talent and passion meet, and where theoretical learning is linked to a potential direction for future development.

Finally, advanced educational technology (AI capabilities) enables new dimensions of personalized learning. AI tools can build large-scale, personalized learning pathways for each student. Using generative AI, a school can tailor unique learning courses based on students’ current knowledge levels, mastered skills, attitudes and values, personal interests, and goals. In this approach, algorithms analyze data reflecting each learner’s unique profile (collected, for example, through assessments, attitude questionnaires and analyses of previous performances) to build content and activity paths aligned with their specific challenges and strengths. Moreover, this technology can identify intersections among different students' learning paths and create opportunities for them to learn together at shared junctures, thus promoting the benefits of collaborative learning and social activities.

The Teaching Domain - The Role of the Teacher as Leader, Developer and Mentor

The role of the teacher in the Real-Life Model undergoes a fundamental change: the teacher shifts from being a lecturer who passes down knowledge to a pedagogue-mentor who supports the personal learning process of each student. Instead of focusing mainly on imparting content, the teacher concentrates on guiding the learner, supporting their learning journey, and processing their experiences into conscious learning. In the new framework, teachers mentor students, with whom they also meet regularly for the purposes of guidance and reflective conversations. For example, at the beginning of every school day, the pedagogue meets with their group of learners. Each student writes daily learning goals for themselves, and the pedagogue helps articulate these goals in terms of knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes. The students then set out on their school day, in accordance with the personal path that was agreed upon and coordinated with the subject teachers. In addition, students’ personal mentors assist their learners in setting annual and multi-year goals.

The teacher in this model serves as a steadfast guide for the student on his development journey. They are mature and supportive figures with whom the students can consult, share their doubts, and receive supportive feedback. In addition to the classroom teacher who serves as a personal mentor, the subject teachers also adopt the role of instructors rather than lecturers. Instead of transmitting knowledge in a frontal manner, they design the learning activities in a way that prompts student engagement and creates a space for independent exploration. This shift requires teachers to transfer a significant portion of the learning responsibility to the learners themselves, and to assume the role of learning designers. In this capacity, they plan environments, projects and experiences in which the students are active participants, instead of focusing mainly on content delivery.

Subsequently, the teacher’s role requires the development of new competencies, such as planning study units centered on competency goals (as opposed to planning a lesson around a knowledge topic), facilitating and cultivating personal reflection, and tailoring instruction to accommodate individual student differences. In summary, two main changes take place: a) A shift from lecturer to mentor-facilitator, i.e., moving the center of gravity of learning management from the teacher to the learner, and from content-based lesson planning to competency-based course design; and b) Designing instruction that integrates components of knowledge, skills, values and attitudes and sets clear competency goals. Both these shifts pose challenges for veteran teachers and require dedicated training and professional development, but they are essential for realizing the vision of the independent and multi-competence learner presented above. This shift in the teacher’s role can be facilitated by an AI-based personal assistant that works with both the teacher and the student.

A personal assistant (bot) that enables implementation of the schoolbag principle in the Real-Life Model: Implementing the Real-Life Model presents significant challenges for the traditional education system. An AI-based personal assistant is designed to address these challenges in the following ways:

Personalization: The personal assistant enables precise tailoring of learning processes to each student’s needs, abilities, and interests.

Continuous monitoring and evaluation: The system tracks student progress in real time, providing immediate feedback.

Complexity management: The personal assistant helps manage the intricacies of competency-based learning.

Teacher support: The system assists teachers in lesson planning, data analysis, and adapting instruction to student needs.

Resource integration: The personal assistant facilitates the effective incorporation of diverse learning resources

Competency development: The system focuses on the targeted development of competencies, monitoring progress across competency components.

The Pedagogical Domain

Learning within the Real-Life Model is founded on the core assumption that competencies serve the learner in real-world contexts; thus, their development should be based on pedagogy that promotes the creation of building blocks and integrated learning, while bridging the gap between education and the real world. The principles of this strategy are:

Interdisciplinary learning focused on competencies: Courses and subjects are restructured to transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries and are designed around clear competency goals. In the Real-Life Model, teaching teams collaborate to design courses or projects that integrate at least four different types of building blocks (knowledge, skills, values, attitudes) that drive learning. Instruction and assessments are planned accordingly. For example, instead of a conventional science lesson, there may be a practical-theoretical course entitled, "Environmental Challenges in the Community." This course would combine ecological knowledge, scientific research skills, the cultivation of curiosity (attitudes) and promotion of environmental responsibility (values) as a single unit. This organization aims to more accurately reflect the nature of real-world problems, which are not confined to separate subjects, thus providing learners with a holistic and applied learning experience.

Real-Life Training (RLT): Recognizing that competencies, and especially their soft components, are developed differently from traditional knowledge acquisition, a significant part of the courses in the Real-Life Model are conducted using RLT methodologies, wherein classroom activities are designed to simulate real-world situations. In these lessons, teachers employ simulations, role-playing exercises (that go beyond the classroom), and on-the-job training (OJT). These activities are selected and crafted to develop specific building blocks that have been chosen by the teacher as part of the proposed course curriculum.

The Organizational Sphere: Reorganizing Learning Time and the School Environment

For multidimensional learning anchored in real-life situations to occur, changes must be made in the organization of the school day and the school learning environment. Several complementary structural changes are proposed as relevant to the Real-Life Model.

Expanding the boundaries of time and space in the school environment: Adopting a systemic perspective of learning time beyond formal class hours and creating connections between learning at school, at home, and in informal settings. The school strives to incorporate the learning events that occur outside its walls into the curriculum and to create encounters where students can experience the real-world dynamic. Thus, there is a blurring of the boundary between "school time," "home time," and "community time." All are perceived as one continuous learning space.

Flexible scheduling and personal choice: The transition from a uniform and rigid schedule to a flexible framework that allows students to choose and personalize their learning experience. With the support and guidance of the educational team, students choose some of their courses or projects based on personal interests and goals. The schedule is based on creating a personal development track for each student that extends beyond school hours, while bridging in-school and outside-of-school learning environments.

Integrating personal learning time into the system: The school schedule reflects time designated for independent learning or guided personal work, during which students engage in personal projects, independent research, or complete individual challenges. These time slots enable students to extract and process their personal building blocks while strengthening areas of weakness and enhancing strengths. For example, the school may allocate weekly time slots dedicated to personal learning; during these sessions, students work independently (under the guidance of their teacher-mentors) or on jointly planned tasks.

Competency-based assessment

To support the development of competencies, school assessment strategies must undergo fundamental changes. Within the Real-Life Model, assessment processes are formulated around the competencies and their components rather than solely focusing on grades given for disciplinary subjects. The school defines the desired graduate profile in terms of competencies and outlines the expected achievements and functions at the end of each educational stage (elementary, middle school, high school) in various competency areas. In addition to standard tests that assess subject knowledge, assessments encompass broader levels ( knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes) as demonstrated through the learner's actions.

A central component of the new assessment strategy is the emphasis on formative and ongoing assessment. Assessments are carried out continuously throughout the learning process, and feedback focuses on the student’s progress in developing various competencies, not solely on the result. Formative assessments of this kind help the learner understand where they stand with respect to each component of competency and identify aspects they have already mastered and those that require further work. For example, the feedback to a student following a multidisciplinary project may be that they demonstrate excellent creativity and theoretical knowledge (knowledge and skill components) but need to be more persevering during teamwork (attitude component). This detailed feedback, focused on competencies, clarifies for the student exactly what to work on next and directs their future steps.

Furthermore, assessments within the Real-Life Model are not solely dependent on the teacher‘s input but are based on the 360-degree principle, providing a comprehensive picture of the student from diverse perspectives; they include assessments of the teacher, the student themselves, the group of learners who learn together with the student, and the AI-based personal assistant working with the student. Moreover, since the Real-Life Model assumes that student development occurs 24/7, assessment and recognition of achievements also include input from external figures, such as a youth movement instructor or extra-curricular coach, and pertain to activities the student engages in outside of school. This process is supported by a dedicated information collection system that is part of the personal AI assistant.

The assessment approach within the Real-Life Model is based on the premise that competencies develop according to the level of maturity of their four components. The degree of development of a competency can be assessed by examining each of the building blocks that constitute it and then integrating the findings into a holistic picture. In other words, to assess a student’s level of competency, one must evaluate the level reached in each of the competency components (knowledge, skills, values and attitudes) related to that competency and synthesize the results. If a particular component remains at the beginner level, the competency is considered not fully developed. These assumptions align with the need to identify specific gaps in learners’ development and provide targeted support. Notably, competency assessment is not simply about the sum of its parts but involves assessing each building block in its own right.

Another important dimension is the qualitative and continuous documentation of progress. Within the framework of the virtual backpack model, the school maintains an up-to-date digital portfolio for each student, where data from all areas of learning is collected. Each significant building block that has been defined - a completed project, a delivered presentation, a demonstrated new skill, or feedback from a social interaction, etc. - is added to the portfolio and classified under the relevant competence. This creates a multidimensional picture of the learner's achievements, rather than a single numerical score. The summative assessment, whether presented at the end of a school year or graduation, reflects a personal competency profile highlighting the student’s key strengths, areas of significant growth, and areas where further development is needed.

A fundamental aspect of assessing competence is the underlying assumption that competence is evaluated in real-world contexts. Thus, the ultimate evaluative test is the ability to identify, define, and solve a complex problem in a real-life setting over time. Moreover, the solution should lead to a productive outcome that can be evaluated, wherever possible.

Expected Benefits and Implementation Challenges

Implementing the Real-Life Model to apply the competency approach can potentially offer many benefits. First, it can improve students’ readiness for the job market: they will graduate with a broad, relevant, and up-to-date set of competencies valued by employers in today’s dynamic world. Instead of entering university or the job market with only theoretical knowledge, graduates will be equipped with value-based approaches and practical skills, such as problem solving, teamwork, effective communication, and independent learning that gives them a clear advantage.

Second, connecting learning to real-life applications increases student motivation. When students see a direct connection between what they are learning in the classroom and their personal lives and future, they are more likely to engage. A student involved in a real project or real-world experience feels that school is preparing them for life, not just for an exam. This sense of relevance inspires deeper and more meaningful learning.

Third, adopting an innovative model such as the “real-life” approach can significantly enhance the school’s image in the eyes of students and parents. A school that actually implements pedagogy aligned with 21st-century realities and fosters entrepreneurship and technological skills, values, and creativity, rather than focusing on rote learning, will be viewed as a relevant, innovative, and valued institution. This can encourage greater parental involvement and public support for school initiatives, ultimately creating an educational ecosystem that works harmoniously to advance its goals. However, it is important to recognize that implementing such a model presents challenges. Schools must undergo fundamental shifts in perception and culture at all levels of the system: among principals, teachers, students, and parents. Teachers in particular require training and support to develop the skills necessary for the new format. Managing project-based learning, conductive alternative assessments, and mentoring students along personalized paths all demand a different set of competencies than traditional teaching. Additionally, broader systemic changes are required. As long as graduation and higher education entrance exams are based solely on traditional academic knowledge, schools will struggle to balance the new with the old. Therefore, reforms in both curricula and national assessment mechanisms are needed to fully support the implementation of the competency-based approach.

Summary

The conceptual revolution from information-based education to competency-based learning, led by international education organizations such as the OECD, is changing the face of the education system in the 21st century. In this article, we reviewed the concept of competencies as outlined in the OECD’s Learning Compass 2030 framework, with its emphasis on integrating knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes in the development of a graduate capable of navigating a complex and unpredictable world. We then explored the practical implementation of this concept in schools through the Real-Life Model, which illustrates how pedagogy can be linked to real-world situations to cultivate competencies in practice.

This discussion describes the pedagogical and structural innovations required when adopting the competency approach. We must teach differently, learn in diverse spaces and times, and use new criteria for evaluating academic success. The Real-Life Model demonstrates possible changes in this direction, such as the concept of 24/7 student development (the backpack principle), the integration of real-world experiences into the learning process; more flexible scheduling and personalized learning tracks; a redefined role for teachers; and 360-degree formative assessment. These changes align with other global trends, including project-based learning, social-emotional learning, and the redefinition of educational success indicators. Finally, it is important to remember that successful implementation of the model requires broad systemic support as well as tailored training and professional development for teachers to help them acquire the competencies needed to teach in this new format. In addition, adjustments to national curricula and external assessment requirements are necessary, along with the engagement of national-level decision-makers. The pursuit of an educational model that develops competencies relevant to the real world is an ongoing journey of learning and adaptation. Like the learners themselves, education systems must also demonstrate proactivity, the ability to resolve dilemmas, and a willingness to take responsibility on the path to shaping a desirable and sustainable future.

References

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. The School Journal, 54(1), 77–80.

Halinen, I. (2018). The new educational curriculum in Finland. Alliance for Childhood European Network Foundation. https://physiart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/The-new-educational-curriculum-in-Finland.pdfDocslib+1allageschoolsforum.cymru+1

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/54ac7020-enOECD

Zahidi, S. (2017, January 4). We may have less than 5 years to change how we learn, earn and care. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/01/realizing-human-potential-skills-jobs-care-work/

Comments